Creative Expression in the Future of Romantic Studies

How might we be creative in our academic communication? Reading time 10 minutes.

This was originally a paper delivered at the National Forum for English Studies, held at Lund on the 10th of April 2025.

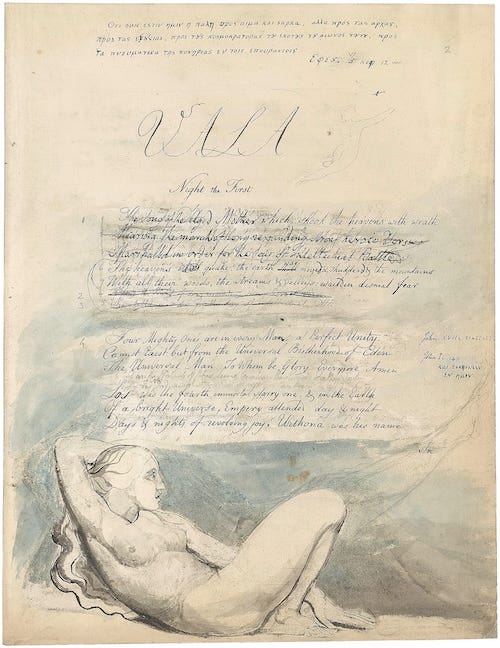

For Romantic artists and writers, it was self-evident that creative expression could contribute to new knowledge about the world around us. Mary and Percy Shelley’s work reflected scientific concerns and hopes about practices like mesmerism and galvanism, and William Blake’s Vala, or The Four Zoas can, as Richard Sha has suggested, be read as an investigation into emerging understandings of the nervous system.

In the period, poets and natural scientists alike worked beyond those disciplinary boundaries that now characterise modern universities, and they communicated their ideas in creative ways. As Amanda Goldstein has shown, the Romantics revitalised scientific poetry as an argument “for poetry’s role in the perception and communication of empirical realities”.1 “They did so”, Goldstein argues, “out of a concern for what of the world would be lost to representation if empirical realities were constrained to manifest in antifigural, antipoetical genres and codes.”2

Today, I think this concern is at least as present as it was in the Romantic age, if not more. As the disciplinarity of modern academia holds fast, are we losing something by constraining the ways in which we communicate research?

Communicating Romantic Studies today

I take as my departure this concern for what will be lost if communication is reduced to the antifigural that Goldstein identifies in Romanticism. This concern can, I think, inspire a reconsideration of how we communicate academic research in today’s world, just as it can force us to consider why we write about the topics we research.

There are many challenges facing scholarship in Romantic Studies, and humanities more widely, today. These include pressure to publish and rising costs to do so, artificial intelligence, but also how to best justify the value of literary research to secure funding, which might include questions of how to bridge the gap between academia and the general public. There are of course no easy answers to these challenges, and I want to bracket what I write here with acknowledging how difficult it is to to imagine exiting futures within the realities of the economic strain the humanities are put under.

However, with that said, I suggest that one possible future for Romantic Studies can be to embrace a kind of Romantic pre-disciplinarity that communicates science and literary criticism in artistic and figurative forms.

This argument comes out of my own interest in incorporating my background in art within my work as a scholar. When I wrote my thesis I was inspired by Aby Warburg’s 1920s investigation into the repetition of symbols in his collage, The Mnemosyne Picture Atlas, and I tried to think of a way to perform a kind of collage in a textual form with my thesis monograph. I also try to find time to paint and illustrate alongside my work, and I’m very inspired by researchers and artists who engage with Romanticism through artistic interpretation.

Romantic literary criticism

What I mean by incorporating Romantic ways of communicating knowledge has to do with intersections between the sciences and the arts, and between artistic production and literary criticism. Literary criticism in the sense that we are familiar with can be said to have begun in the Romantic period. Reviewers like William Hazlitt and other magazine writers practiced and discussed literary criticism, as did poets like Robert Southey, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and William Wordsworth. While literary criticism was emerging as a distinct profession that did not require its practitioners to be artists themselves, many poets and artists were still actively involved with that kind of writing. For many Romantics, artistic practice and critical thought informed each other.

Thinking in verse

Simon Jarvis has written about how Romantic poets Wordsworth, Blake, and Percy Bysshe Shelley thought in verse. For these poets, Jarvis suggests, “thinking was not something which naturally first of all happened in prose, and which then had somehow to be put into verse. It was instead something which could happen in verse too, and would happen differently if it did.”3 Thinking in poetry can bring new kinds of thought. Jarvis continues to suggest that this might be an under-explored avenue in literary criticism:

“their thought and work may remain far in advance of any literary-critical apparatus which has so far been brought up to decode them…verse is not merely a kind of thinking but also a kind of implicit and historical knowing: the possibility that the finest minutiae of verse practice represent an internalized mimetic response to historical changes too terrifying or exhilarating to be addressed explicitly.”4

For me, this idea that verse or other forms of figurative language can maybe produce knowledge and open up alternative ways of communication seems like an interesting road for future academic criticism. Might we learn something about Wordsworth’s poetry, for example, if our academic writing about it was in verse?

Creativity in academic writing

This brings me to the question of creativity within academic writing. When teaching academic writing to students, I sometimes emphasise that it is a form of creative writing. The students, who have to learn everything they can about topic sentences and three-part essays might not always believe me, but I think all of us who work within academia can see the creative elements of this kind of prose writing. There’s a kind of satisfaction when you can get across what you want to say in a nice way, all the while working within the rigorous constraints often put on academic writing.

One of the reasons we often give against academic writing to students is that AI removes the very necessary creative process of thinking through writing. We need to write to produce our knowledge. If we emphasise creativity within academic writing we might be able to showcase the value of human-produced research, but we must then also place academic writing closer to other forms of creative textual production, both in prose and verse.

Criticism as art

To think about the process of academic writing as inherently valuable is to consider it a form of artistic practice. Stepping away from the Romantic era for a moment, this brings to mind Oscar Wilde’s 1891 “The Critic as an Artist”, his response to writers like Matthew Arnold’s understanding of the relationship between criticism and art. In a Socratic dialogue between two men, Wilde presents the argument that criticism is not only an “echo” of art, but that criticism is an artform in itself, just as art is dependent on critical thought. Criticism, like art,

“works with materials, and puts them into a form that is at once new and delightful…For just as the great artists, from Homer and Æschylus, down to Shakespeare and Keats, did not go directly to life for their subject-matter, but sought for it in myth, and legend, and ancient tale, so the critic deals with materials that others have, as it were, purified for him, and to which imaginative form and colour have already been added.”

Wilde’s defender of the critic as artist goes on to suggest that criticism is an end to itself that has more to do with recording the critic’s soul. This is of course not necessarily what we would consider to be the purpose of literary criticism today, as we instead strive to elucidate a work’s position within a set of ideas, contexts, or networks. But I think we are at the same time more aware about the researcher’s bias and subjective interpretation than before. In a way, our research is a record of our minds, or of our souls.

This increased awareness of interpretative bias among researchers can lead to a reconsideration of the critic as artist that is similar to Wilde’s text, or similar to the intersection between criticism and art present in the Romantic poets’ life and work.

On the one hand, it can push us towards finding alternative methods of communication that allows for multiple interpretations by our readers. On the other, we can perhaps lean into it, and produce new literature and art that veers more, or entirely, towards artistic interpretation

Encouraging multiple interpretations

The reconsideration of subjective interpretation is gaining ground internationally within digital humanities projects. One example within Romantic Studies is the project Romantic Europe: The Virtual Exhibition, led by Catriona Seth and Nicola J. Watson. This project fosters connections between what has otherwise been seen like disparate expressions of Romanticism across Europe, and to appeal to both an academic audience and to the general public. The virtual exhibition was conceived of as an “imaginary museum” that could be used for heritage organisations, teaching, and research.5

The kinds of projects allows the viewer to browse material in whatever order they like and draw their own connections. They avoid the promotion of one single argument, or one line of thought. They are one way to overcome the challenge posed by the lack of access to academic journals for general readers and the challenge of trying to show how Romantic Studies can engage with a wider community.

The imaginary museums are creative in the sense that they offer an impression without a strict interpretation, responding to this idea of the researcher as a creative agent by putting the task of narrativization and interpretation onto the viewer instead.

Vala

Perhaps inspired by Blake’s own independent printing and non-traditional approaches, The Blake Society regularly publishes Vala. Each issue contains shorter academic texts, but also visual art and other creative responses to Blake’s work. The works essentially are communications from artist-to-artist, from the 21st-century artist-critic to the Romantic-era Blake. It levels the discussion, in a sense, between these two voices.

And perhaps, like the Romantics thinking in verse, it can achieve another kind of knowing, another way of approaching something in Blake’s work that is not easy to capture within conventional academic writing.

It also encourages a different kind of critical engagement from its readers. As academics we usually respond to other’s articles and provide counterarguments, but here we can also critically interpret a new work, and choose whether we want to be bound to how the work responds to Blake, or whether we would like to read it fresh, unbound from intertextual allusions.

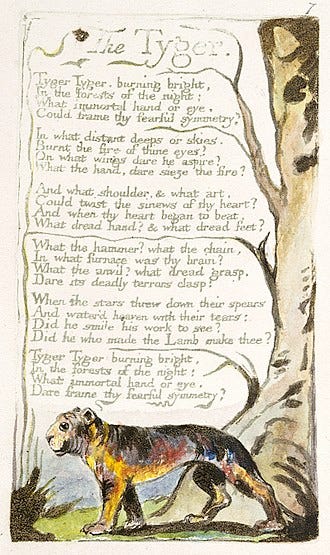

Taking page 71 from a recent issue as an example: this page features the poem “What Dread Hand” by MJ Millington, a Connecticut-based poet and artist, alongside an illustration by Tamsin Rosewell, and illustrator and historian. The poem and picture both clearly responds to Blake’s “The Tyger” and can be read for what they interpret into that famous poem. The speaker in Millington’s poem seems to address the same tyger as Blake’s speaker does, and they recount that conversation from so long ago. But instead of continuing to question the tyger, as Blake’s speaker does, the second stanza of Millington’s poem becomes more introspective. “Whatever the hand that dared frame you, ours the dread hand that unframes.” The speaker undoes the tiger in verse to bring forth the question that is implicit in Blake’s work: “Who made us?”. The illustration, with the woman stepping on top of the tiger to reach the sun, seems to visualise this use and undoing of the animal by humans for understanding our own nature.

But the picture can also be read outside of Blake’s world. The fire seems to run through the painting. The dead trees seem aflame from the red -hot sun, whose flames surround the human figure. Her hair, and the tiger’s fur, repeat these flames and their colour. Unbound from Blake’s “The Tyger”, Rosewell’s illustration can be read in relation to the climate crisis, as a representation of humanity reaching up towards a sun that is already on fire, in a dead and blackened world, trampling on endangered wildlife.

The kind of engagement encouraged by a publication like Vala turns academic criticism more into a conversation between creators. We become, like the Romantics, artists and critics in one, talking to each other.

I think this kind of creative expression is one way in which Romantic Studies can show its continued relevancy in today’s academic environment, while at the same time producing work that can bridge disciplinary boundaries and engage with both an academic and non-specialised audience.

This would mean nearing ourselves to the practices of the Romantics, becoming critics-artists who further recognise the creativity inherent within literary criticism.

Amanda Goldstein, Sweet Science: Romantic Materialism and the New Logistics of Life (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017): 6

Goldstein, Sweet Science, 11

Simon Jarvis, “Thinking in verse”, The Cambridge Companion to British Romantic Poetry, eds. James Chandler and Maureen N. McLane (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2008): 98–116 (98).

Jarvis, “Thinking in verse”, 99.

Catriona Seth and Nicola J. Watson, “Introduction: Material Romanticism”, Romanticism on the Net #80–81 (Spring-Fall 2023).